A deep dive into Ready Player One and the ways we cater to specifically male nostalgia.

As a woman and a feminist, my relationship with pop culture is inherently going to be a love/hate one. Partly because pop culture keeps screwing its representations of women, gender relations, sex, etc., but primarily because for most of my life (and still for a lot of the current period) pop culture wasn’t created for me. Pop culture was largely created by and for men, and if women happened to also like it, great, bonus viewers without trying! Or small subsets of pop culture would be created for girls and women, but rarely with the care and attention that was given to content created for men and boys, and our relationship with pop culture was not granted the same respect.

I’ve been thinking about this uneven relationship a lot lately. In part this is because of the way that the box office and critical reception for Black Panther and A Wrinkle in Time have essentially been pitted against each other: as if the fact that they were both created by black directors with primarily or largely black characters overwhelms the fact that they were created on different budgets for different audiences. It’s also in part because of the upcoming release of the film version of Ready Player One, and because of a recent video essay about that film by Lindsay Ellis.

I’m going to use the latter to dive deeper into what it says about catering to men’s versus women’s nostalgia, because a critical discussion of the comparison between Black Panther and A Wrinkle in Time is just going to give me a headache right now. Go see both movies. Yes, A Wrinkle in Time is supposedly not good and isn’t faithful to the book, but you know damn well that five years from now, “movies based on books that aren’t faithful to the book do poorly” is not going to be the narrative around its failure any more than the narrative around Catwoman’s failure was “movies with shitty scripts do poorly.” The narrative will be “major movies entrusted to black lady directors with ladies of color in the cast do poorly.” So go see the damn movie so we don’t have to have that exhausting and incorrect conversation.

Anyway, I first read Ready Player One at the request of a friend. He’d said he really liked the novel, but that something had felt off about it, and he wanted my opinion on it. I read it over the course of a plane ride, and texted him when I had landed. I don’t remember what exactly I said, but it was something to the effect of feeling as if the book was supposed to have been written for me, but that something had gone wrong in the process. The uncertainty was akin to feeling the whoosh of a metaphorical arrow as it went past my shoulder—I was close to the target audience of Ready Player One, but not quite there.

I pondered those feelings for a while, and to be honest I’m still untangling them. But the end result was this: the book wasn’t written for me. It wasn’t really written with a female audience in mind, period. It was written by a well-meaning man (I’ve had the pleasure of meeting Ernest Cline in person and can confirm that he is a very nice, very (ha) earnest geek) who included women and people of color as an afterthought, or as an intended bonus that he didn’t really think through. Ready Player One is, in its purest form, the distillation of the white, straight, cisgender male geek experience. The fact that my own life experiences have overlapped with that experience enough for me to also enjoy the book is an unintended bonus.

Better people than me have written on the problems with the characters of Art3mis and Aech, including Beth Elderkin and Lindsey Weedston. But I will summarize.

The main character, Wade, is the Nice Guy in his truest form. (Don’t take my word for it, he even calls himself “a really nice guy” in the book.) He’s the poor, unpopular kid who everyone overlooked until it turned out he was super awesome, and that his very particular skillset, which would win him no prizes in the real world, is actually way important in the virtual world. He is the geek made good. He is literally the White Knight—his username in the OASIS is Parzival, one of the Knights of the Round Table.

And like most nice guys and white knights, his shine comes off the more you get to know him. He cyber-stalks Art3mis before ever meeting her. He objectifies Art3mis at the same time he idolizes her for “not being like other girls.” When Art3mis turns down his affections, he moves on to actual stalking, including having his avatar hold a boombox up to her window. When he finally finds out her big secret (*spoiler*) that she has a birthmark on her face, he is manly enough to “overcome” her disfigurement and love her anyways. And then I threw up a little in my mouth.

Art3mis, meanwhile, comes so, so close to being something besides a quest object, only to fail, hard. She starts off as a fully realized character—a fellow searcher who has her own active social media life, and at the start of the book, she is actually better at questing than Wade is. However, all of this character development quickly falls apart. Wade soon shows her up at questing, firmly slots her in the role of love object and supporting character, and makes her a trophy just as much as the keys and eggs of the OASIS. At the end of the story I find myself really wishing that Art3mis had the powers of the actual Artemis’ (you know, the virginal goddess of the hunt) and could turn Wade into a deer that got ripped to pieces by dogs. Come on, it’s a little violent, but no one would have seen that ending coming.

And honestly, Art3mis gets a boat load of character development compared to Aech, Wade’s best friend who we find out (way, way late in the book, spoilers again) is not actually the Caucasian male that Aech presented as in the OASIS, but is actually an overweight, black, lesbian woman. (I honestly don’t know if the lesbian part was added to be part of the tokenization trifecta, or so that we could have a super awkward exchange where Wade realizes that he’s been talking to Aech for a long time about how much he likes certain girls, but it’s totally okay because Aech also likes girls.) We get a brief moment of a really, really interesting idea with Aech—she reveals to Wade that she presents as a white male because she is more likely to get respected that way, even in the supposed equalizing utopia of the OASIS. For every female gamer who has ever created a male character in an MMORPG in order to avoid getting sexually harassed, this is a familiar concept with huge implications for the world of Ready Player One. What does it mean for the promise of technology if technology only replicates oppression instead of solving it? How might the perceived perfection of virtual reality lead to more internalized misogyny, homophobia, racism, and fatphobia? Is there a way for a virtual world to truly be “better” than the real world? How could we use virtual reality to help us gain empath—oh, we’re only 50 pages from the end of the book? And we’re literally never going to address any of these topics, and we’re only going to vaguely continue addressing the fact that Aech is an overweight black lesbian? Oh, ok. Cool. Never mind.

And again, don’t get me wrong—I still do like a lot of the book. It is fun for me as a geek to indulge in this nostalgia-fest. But that is because, like Art3mis in the novel, I have grown up to enjoy pop culture that is filtered through a male lens. Beth Elderkin explains,

I enjoy the book because I enjoy a lot of the things that the book’s male author, and his male protagonists, enjoy. I genuinely enjoy Monty Python, old-school arcade games, Star Trek, Japanese robot anime, etc. But that isn’t all that I enjoy, and it’s not all the nostalgia for the 1980s that is possible. It’s just the specifically male nostalgia. And again, trying to give all possible credit to Ernest Cline, I don’t think that he wrote this book with the specific intention of discounting women or female nostalgia. I think in his own mind, he really wrote a book about “universal” nostalgia. But in the same way that medical practices are androcentric, making the male body the norm, popular culture and popular nostalgia is androcentric too, making make interests and desires the norm. If a male author doesn’t question this androcentrism, it feels totally normal and reasonable for that author’s experiences to seem universal, even when they aren’t.

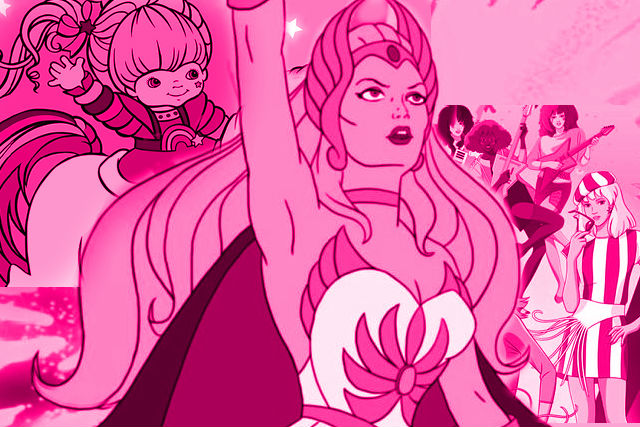

This hit home when another friend showed me a satirical Youtube video, “Ready Player One for Girls” by Jenny Nicholson. Nicholson explains that since she’s not a man in her mid to late thirties, “all of these super obscure 80s references” went over her head. Luckily, she was able to get the Ready Player One girl translation (complete with sparkly pink cover) with nostalgic pop-culture references that she could understand. She reads a few “passages,” essentially recreating the text of Ready Player One but with girl-centered references instead of guy-centered ones. Gail Carson Levine, Stephanie Meyer, Teen Witch, Legally Blonde, Gary Marshall movies, and Lady Lovely Locks all get shout outs. (Also, I may have exclaimed out loud in joy because someone besides me remembers Lady Lovely Locks.) As do Rainbow Brite, Sailor Moon, My Little Pony, and Neopets. Nicholson hits on one of the core attributes of Ready Player One when she exclaims “reading lists of things I recognize is pretty fun.” Later, the main character hits a virtual reality nightclub on a steed that combines She-Ra, Jem and the Holograms, hit clips, friendship bracelets, and Lisa Frank.

When I first started to watch the video, one of my instinctive thoughts was “this is so ridiculous.” And then I examined that thought. Because it is only as ridiculous as Ready Player One. It is the exact same concept, only filtered through female nostalgia instead of male nostalgia. But even as a woman, I have been taught that the properties women are nostalgic for, or even women’s inclusion in nostalgia, is ridiculous. And when this nostalgia does happen, it is rarely accepted or successful.

The female-centered Ghostbusters film, despite being a pretty decent flick, broke the internet and enraged the fanboys. My Little Pony succeeded on a massive scale, but a large part of that is due to its unexpected male audience. Nostalgia revivals like Gilmore Girls and Fuller House have had to flee to Netflix, whose algorithms are seemingly a bit gentler regarding female viewers than the strict Nielsen ratings. The Jem remake resembled its original so little and was so obviously broken that it was yanked from the theaters within a couple of weeks. The Powerpuff Girls reboot was a half-assed dumpster fire that didn’t seem to understand why the original worked. And the upcoming Heathers reboot looks like it’s going to be what happens when you take one of the least nuanced storylines of recent South Park memory (sometimes people who care about being PC can become oppressive themselves!) and then make a show about it where we’re supposed to root for the poor cisgender white people who are afraid of all the mean homosexuals, genderqueer people, and women of color.

Even when girls are present in properties that run on nostalgia, they are often sidelined either in the property itself or in the marketing. Paul Dini has acknowledge that networks frequently dismiss or actively avoid girl-centered storylines in superhero properties. While shows like Stranger Things have female characters that are actually well-written and complex, they’re still effectively sidelined for male storytelling. Hell, even when the nostalgia-fest is about them they don’t get any due. One of the most nostalgia-friendly, ‘member berries downing movies of the last decade, Star Wars: The Force Awakens has a female protagonist. That’s not just my opinion, that is literally how the movie works. But Rey was frequently sidelined in merchandising, to the point that she wasn’t even included as a figure in the branded version of Monopoly that they released.

We can even see this in one-to-one comparisons of similar properties. The Xena reboot that promised to feature an explicitly queer relationship between Xena and Gabrielle died before it could live, even though we got two goddamn Hercules movies in the same year. We had at least four dudes play Batman before we got a Wonder Woman movie.* People who were born when the first X-Men movie started to kick off the superhero renaissance will be old enough to vote before we get our first female-led, solo Marvel movie.

All of this emphasizes the idea that mainstream pop culture is not really meant for or aimed at women, but two of these in particular, the Ghostbusters film and the studio execs actively fleeing female audiences, point to something else that is equally insidious: things are considered worse when girls and women like them.

Marykate Jasper had an interesting article comparing Ready Player One to Jupiter Ascending. Jasper does not defend Jupiter Ascending for being a good movie (it’s not) but her argument was that it was just as trashy and wish-fulfilment-y as Ready Player One, but that it was taken way less seriously and given much less credit because it fulfills the escapist fantasies of girls instead of boys. Back on our old site, our guest writer Amelie was making that point before it was cool:

To be totally honest, the plot of Jupiter Ascending is pretty much equal in wish fulfillment, bizarre plot, and special snowflake characters when compared to Ready Player One. And while Jupiter Ascending relies on aspects stolen from almost every sci fi story and fairy tale that has come before it, it at least has the decency to leave this in the realm of homage, instead of literally saying “hey, remember Power Rangers? Aren’t Power Rangers cool? I have Power Rangers in my movie.” But Jupiter Ascending is going to be remembered as an incredibly expensive flop, while the buildup around Ready Player One has already basically guaranteed that it will at least make its money back. And as Amelie pointed out, at least in the very expensive flop, the female protagonist had some damn agency.

This discussion of things being worse because girls like them is central to a recent video essay by Lindsay Ellis that reexamines Twilight. While I personally think that Ellis glosses over some of the more legitimate reasons to dislike the franchise (namely the way it romanticizes a deeply unhealthy and abusive relationship and emphasizes an abstinence-only message where the woman is mindlessly needy and the man has to be stoic and deny her desires) she makes some excellent points about the overwhelming hatred aimed at the book and its fans. (She also takes some swipes at Ready Player One. Look at me, pulling strings together. It’s like I know what I’m doing when I write things.) She points out that as a culture, we have extra disdain for teenage girls and basically anything that they like, and we actively encourage girls to distance themselves from one another in order to be respected.

I will admit to being one of the people that Ellis discusses, a young woman eager to distance herself from a cultural phenomenon that was unapologetically embraced by teenage girls. I’ve had to process a loooooot of internalized misogyny that stems from early experiences of being shunned and misunderstood by the “popular girls” and feeling as if I didn’t “fit in” as a girl. Now I can recognize this as early signs of rebellion against gender norms, but for a long time, it was “not-like-other-girls-itis” where I disliked what I couldn’t understand within my own gender. So while I do maintain that while a good portion of my disdain for the book series comes from a legitimate place (the writing is bad, the pacing is terrible, and again, the aforementioned serious, serious problems with the relationships it portrays) I can and do admit that I was likely more vicious towards it than I would have been towards male-centric books of equally poor quality. Both because I was trying to distance myself from other girls, and because I was fairly ashamed that of all the quasi-trashy supernatural romance novels that were aimed at young girls, it was the worst of them that exploded into popularity and became representative of What Girls Like. (There are so many better quasi-trashy supernatural romance novels. I have read them.)

So where does this leave us? Well, depending on who we are, it leaves us with a few tasks.

For audience members of all gender persuasions, it means we have to come to an agreement: we either have to universally raise our standards on pop culture and dismiss wish-fulfillment quasi-trash of all types, or we have to agree to be kinder to the work of that type that features and is aimed at girls and women. We have to be equal opportunity consumers of mindless entertainment. It also means we need to show up, and show demand, for things that cater to traditionally female interests. We also have to stop demeaning female fans, especially teen girls, for being passionate about things.

On the production side, it means that media organizations need to start cultivating female fans. Not just creating things that will only appeal to a narrow spectrum of girls, or things that will appeal to girls by default, but start actively courting a broad female audience in the same way that a broad range of men and boys are appealed to in various media creations.

Girls should have their Ready Player One. Girls should have their Transformers. They should be able to have debates over who was the “best” cinematic Wonder Woman, or the best incarnation of a female-led spy franchise. They should be able to quote the movies they watched as teens and have an entire room say the next line to them.

They should be able to love, and be loved by, pop culture.

Signed: Feminist Fury

***

*For you nitpickers, four discounts West and Affleck because they were roughly contemporaneous with Carter’s and Gadot’s Wonder Women, respectively.

Featured image is a collage of 80s nostalgia figures Rainbow Brite, She-Ra, and Jem and the Holograms. All characters belong to their original rights holders.

Growing up with gaming (my first console was Pong and I’m still an avid gamer in my 50s), I suppose I still felt a lot of the nostalgia in the movie (I haven’t read the book). So I had a lot of fun watching it the other night. That said, on reflection, I would have loved it more if Art3mis had been the lead character, or they had been competitors – and yes, maybe if she beat him to the egg but then shared it with them anyway. I don’t know. Maybe I ought to go away and write the book I’d want to read more?

I would have loved if there had been more woman-centred storylines in gaming. Not that I didn’t love all the games that were out there, but Tomb Raider was probably the first game where I felt connected to the character as a woman (kick-ass, solves her own problems, etc), even if Lara had been designed with the male gaze in mind. Prior to that, I’d had to play all my favourites as a male character because that’s the way they were designed. I’m at the point now where I’ll refuse to buy a game that doesn’t have a female avatar choice for the main character, even if I would love the game (The Witcher, The Last of Us). Cutting off my nose to spite my face, maybe, but if I can’t play a character that represents me then fuck them, they can’t have my money.